Can You Get Spontaneous Pneumothorax Again

- Example report

- Open up Access

- Published:

Recurrence of spontaneous pneumothorax six years after VATS pleurectomy: evidence for formation of neopleura

Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery book 15, Article number:191 (2020) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Main Spontaneous Pneumothorax (PSP) is considered an accented and definitive contraindication for scuba diving and professional flight, unless bilateral surgical pleurectomy is performed. Only then is there a sufficiently low risk of recurrence to allow a waiver for flying and/or diving.

Example presentation

A immature fit male patient who suffered a PSP half dozen years ago, and underwent an elementary videoscopic surgical pleurectomy, presented with a complete collapse of the lung on the initial PSP side. Microscopic exam of biopsies showed a slightly inflamed tissue but otherwise normal mesothelial cells, compatible with newly formed pleura.

Conclusions

Even with pleurectomy, in this patient, residue mesothelial cells seem to have had the chapters to create a completely new pleura and pleural space. The nearly appropriate surgical technique for prevention of PSP may still be debated.

Background

Master Spontaneous Pneumothorax (PSP) is considered an absolute and definitive contra-indication for scuba diving [i]. An exception could exist made if bilateral surgical pleurectomy is performed, with resection of any visible bullae or blebs, so only if no further structural or functional abnormalities are found (on high-resolution CT scan and extensive pulmonary function testing) [one,ii,iii]. Video assisted surgical pleurectomy (Video Assisted Thoracic Surgery - VATS) is nowadays considered the treatment of choice for these patients, as information technology offers a very low risk of recurrence for adequate surgical morbidity [iv, v]. Information technology is thought that surgical pleurectomy, with removal of almost of the parietal pleura by sharp dissection and forceps peeling, has a lower recurrence rate than simple abrasion of the parietal pleural surface, every bit in the one-time, all pleura is stripped from the thoracic wall, producing fibrous scar tissue which completely obliterates the pleural cavity [6,7,8]. However, owing to the invasive nature of this procedure (which must be done bilaterally), not many divers take this step; therefore, follow-up information for divers is very scarce. Nevertheless, if this intervention were found to neglect in its principal purpose, the current recommendations may have to exist revised.

We present a instance of ipsilateral recurrence of PSP in a immature male, 6 years after the initial event, which was treated with VATS pleurectomy.

Instance presentation

A 31-year old, fit, salubrious male, an occasional smoker, suffered acute astringent correct thorax hurting during a bicycle bout. Clinical exam and chest X-ray revealed an of import right-sided pneumothorax, which was treated with unmarried-needed aspiration and was fully deployed after aspiration of 510 ml. However, a control X-ray after 36 h revealed a full recurrence with on expiration film a slight deviation of the trachea and upper mediastinum. Therefore, and because many of the sports activities the patient participated in involved atmospheric pressure changes (skiing, diving, flying), it was decided to proceed to surgical pleurectomy. This was performed with a classic three-channel VATS, in the 6th and 8th intercostal space. The parietal pleura was surgically stripped from the first rib, forth the sympathetic nerve chain, to the diaphragm and along the internal mammary avenue. No blebs or bullae were visualized. The suction drain was clamped on the fifth postoperative mean solar day, but because of a minor apical loosening, suction was resumed for some other 5 days. At that signal, a control 10-ray was normal and the suction drain was removed at mean solar day ten. The patient was able to fully resume working activities later 1 month. Pulmonary role tests were performed after 3 months and showed normal values (Vital Chapters 110%, FEV1 at 115%, DLCO 90% and Transfer Coefficient (DLCO/Alveolar Book) of 99%.

Six years later, at residuum, he over again experienced some discomfort in the right chest cavity, which manifested mostly as dyspnea and some physical limitation during running. In hindsight, this chest discomfort may have started after having attended a pop concert a few days earlier. After a few days (considering of the weekend) he sought a medical consultation and a chest Ten-ray once more showed a consummate collapse of the right lung.

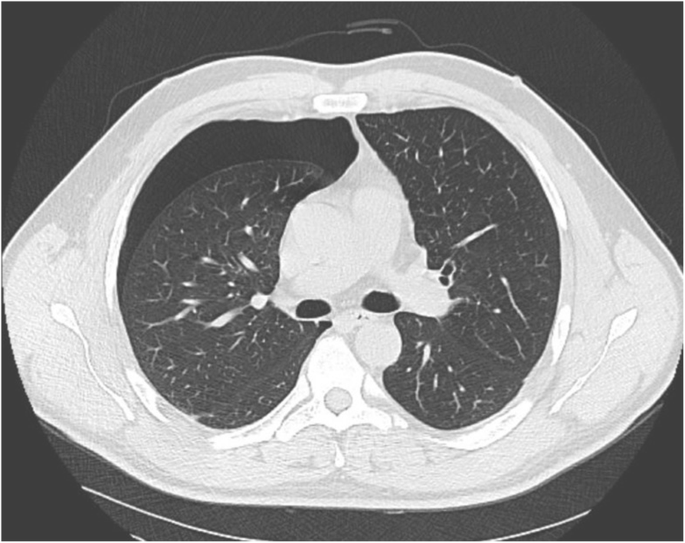

A CT-scan confirmed a complete right-sided pneumothorax, with no adhesions in the pleural infinite, compression of the right lung and deviation of the mediastinum towards the left. A modest subpleural bulla was identified in the superior and junior lobes (Fig. 1).

Recurrence of pneumothorax 6 years afterwards VATS pleurectomy

A new thoracoscopic intervention was performed, with resection of the correct apex, and prelevation of biopsies, prior to consummate parietal surface scarring and chemical (talcum powder) pleurodesis. The postoperative grade was uneventful. Examination of the biopsies showed the presence of reactive hyperplastic mesothelial cells on the parietal side, compatible with neo-pleura.

Discussion

Primary Spontaneous Pneumothorax is defined as collapse of the lung without obvious external trauma. It is most frequently observed in young male patients, by and large smokers, and is idea to consequence from structural abnormalities in the lung or pleural tissue, with or without radiological or visual evidence of pulmonary blebs or bullae [4]. The risk of recurrence is loftier, either ipsilateral (16–52% within the outset year) or contralateral (12.5%) [ix]. Therefore, a simple needle aspiration or chemic pleurodesis are considered insufficient to provide acceptable protection should the individual be involved with critical activities involving environmental force per unit area changes. As an case, should a pneumothorax occur during scuba diving at a depth of just 10 m, the expansion of the extrapulmonary air during rising to the surface would entail a doubling of its volume (Boyle'due south Law), possibly provoking a severe and life-threatening tension pneumothorax. Similarly, professional (war machine) pilots may be prohibited from resuming their duties after PSP unless a more than definite (surgical) procedure has been performed [ten,11,12]. However, it is recognized that while the risk is sufficiently low to allow resumption of these activities (estimated at 0.five%), it is still somewhat higher than in the reference population. Estimation of this chance is rendered difficult by the variable terminology used to describe the process. For example, the thoracoscopic administration of talcum powder or tetracycline is technically a chemical pleurodesis administered in a surgical manner, and then may be chosen 'surgical pleurodesis'; however, the same name is given to a mechanical chafe of the parietal pleura through thoracoscopy, besides every bit to VATS pleurectomy, which is a partial removal of the parietal pleura by means of incision and forceps. From the current literature, it is virtually incommunicable to distinguish the recurrence rates for each of these three interventions (or more if combinations are used) [13, fourteen].

Chemical or mechanical pleurodesis provokes an inflammatory state in the pleura, inducing the germination of adhesions, besides because of fibronectin formation past injured mesothelial cells. Later on a period of iii to 4 weeks, fibrosis of the pleural crenel occurs [fifteen].

By surgically removing the parietal pleura, a raw, haemorrhage surface is created which subsequently heals past scarring with consummate removal of parietal pleura structures and this is the main reason why, in divers and aviators, pleurectomy would exist preferred over chemical pleurodesis or scarring of the parietal pleura. This would let the pleural infinite to be completely obliterated without a possibility for re-cosmos of a virtual pleural space [seven, sixteen]. In nature, simply ane species of mammal, the elephant, has evolved such a gristly construction in lieu of a 'virtual space' pleura, allowing them to use their trunk as a snorkel, and breathe at much higher negative pressures than is possible in humans. Elephants cannot develop pneumothoraxes [17].

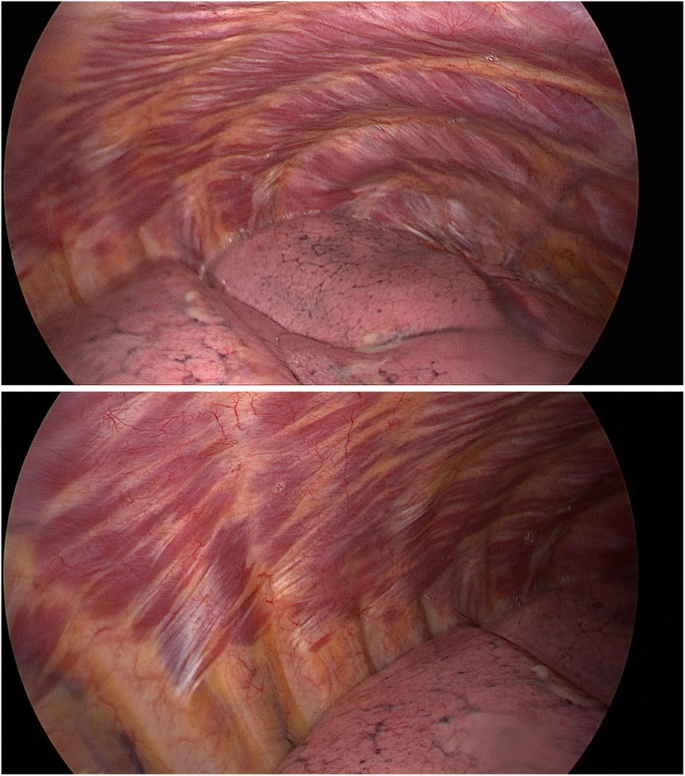

When recurrence of pneumothorax happens after pleurodesis or pleurectomy, it is oftentimes partial and attributed to incomplete scarring [xviii]. However, in our patient, a complete collapse of the lung at the pleurectomised side was observed with no evidence of pleural adhesions (Fig. 2), and pathological exam of the biopsy specimens showed near-normal pleura on the parietal wall. This development of a "neo-pleura" has, to our noesis, not been described previously.

Videoscopic images of chest cavity prior to 2nd process: no pleural adhesions visible

Possible gamble factors for recurrence of pneumothorax after surgical intervention include rest blebs or bullae on CT browse [19], non-smokers [20], persistent air leak (PAL) after the initial drainage or pleurodesis procedure [21, 22], female sexual practice [21], historic period younger than 17 years [22] and use of anti-inflammatory medication subsequently the procedure [23].

Our patient had no visible bullae during the kickoff intervention; all the same, no CT scan was performed prior to the intervention. A PAL was diagnosed after unproblematic aspiration (complete recurrence subsequently 36 h) and fifty-fifty after pleurectomy, suction had to be prolonged for a full of ten days before sealing was achieved. The patient continued to (occasionally) smoke. As the get-go process was performed by one of the authors (TO) we can confirm that the pleurectomy was complete and that in that location was virtually no residuum parietal pleura after the procedure. Neither the CT browse nor the endoscopic image during the second procedure showed adhesions, something which would have been likely in case of previous incomplete pleurectomy.

Information technology is not known whether our patient had taken Non-Steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) for pain relief afterwards the outset operation. The standard procedure for pain relief in our hospital consists of paracetamol orally or intravenously. Daily administration of diclofenac has been shown to significantly subtract the charge per unit of collagen degradation, fibrosis and adhesion formation in a porcine model of mechanical pleural abrasion [15]. The effects of NSAIDs on the scarring procedure afterwards pleurectomy take not been studied as such, but in wound healing their negative effects have been demonstrated conspicuously in animal models, and have been attributed to their power to suppress prostaglandin synthesis, a central requirement for inflammation [24, 25]. However, the detrimental effect on pleural scarring has still to exist confirmed in humans [26, 27].

Two recent reviews [28, 29] concluded that over a large cohort of patients who had benefited from a diverseness of combinations of procedures and followed upwardly to 10 years subsequently, the lowest risk of recurrence was seen in the group 'VATS wedge resection + chemical pleurodesis with talcum' and 'VATS wedge resection + pleural abrasion + chemical pleurodesis with talcum'. The advantage of this latter combination would exist that a maximal surface can be treated and that surgical (bloody) pleurodesis is enhanced with a chemical irritative reaction. At least in the brusk- to medium term (2.5 years), risk of recurrence seems similar between 'pleurectomy' and 'pleural chafe + chemical pleurodesis' [30].

Conclusions

Our observation suggests that even a very minor number of residual pleural cells may regenerate a complete pleura after VATS pleurectomy. We suggest that video assisted wedge resection, followed past pleural abrasion and chemic pleurodesis may be a more reliable choice for defined, rather than VATS pleurectomy alone.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- PSP:

-

Primary Spontaneous Pneumothorax

- VATS:

-

Video Assisted Thoracic Surgery

- FEV1:

-

Forced Expiratory Book in one s

- DLCO:

-

Diffusion Capacity for the Lung of Carbon Monoxide

- CT:

-

Computed Tomography

- PAL:

-

Persistent Air Leak

- NSAID:

-

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug

References

-

British Thoracic Lodge Fitness to Dive Group SotBTSSoCC. British Thoracic Society guidelines on respiratory aspects of fitness for diving. Thorax. 2003;58(ane):three–thirteen. https://doi.org/10.1136/thorax.58.1.3 PMCID: PMC1746450.

-

The medical test and assessment of commercial divers (MA1)2015 April 20, 2018. Available from: http://world wide web.hse.gov.uk/pubns/ma1.htm.

-

Pneumothorax and its consequences. DAN SEAP Alert Diver. 2005 Apr 20, 2018. Available from: https://www.danap.org/DAN_diving_safety/DAN_Doc/pdfs/pneumothorax.pdf.

-

Noppen M, De Keukeleire T. Pneumothorax. Respiration. 2008;76(2):121–seven. https://doi.org/ten.1159/000135932.

-

Treasure T. Minimally invasive surgery for pneumothorax: the prove, changing practice and electric current opinion. J R Soc Med. 2007;100(nine):419–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/014107680710000918 PMCID: PMC1963389.

-

Addas RA, Shamji FM, Sundaresan SR, Villeneuve PJ, Seely AJE, Gilbert South, et al. Is VATS Bullectomy and Pleurectomy an effective method for the Management of Spontaneous Pneumothorax? Open J Thor Surg. 2016;06(03):25–31. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojts.2016.63005.

-

Chang YC, Chen CW, Huang SH, Chen JS. Modified needlescopic video-assisted thoracic surgery for primary spontaneous pneumothorax : the long-term effects of apical pleurectomy versus pleural abrasion. Surg Endosc. 2006;xx(five):757–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-005-0275-half dozen.

-

Min X, Huang Y, Yang Y, Chen Y, Cui J, Wang C, et al. Mechanical pleurodesis does non reduce recurrence of spontaneous pneumothorax: a randomized trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98(5):1790–6; discussion six. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.06.034.

-

Sadikot RT, Greene T, Meadows K, Arnold AG. Recurrence of primary spontaneous pneumothorax. Thorax. 1997;52(9):805–9. https://doi.org/ten.1136/thx.52.nine.805 PMCID: PMC1758641.

-

DoD Directive. AR 40–501 Standards of Medical Fitness2007 April eighteen; 2018. p. 45. Bachelor from: https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=XfaTCgAAQBAJ&pg=GBS.PA45.

-

Lim MK, Peng CM, Chia KE. Spontaneous pneumothorax occurring in flight. Singap Med J. 1985;26(1):93–five.

-

Respiratory guidance fabric: Implementing Rules, Adequate Means of Compliance and Guidance Cloth on respiratory conditions2015 April 20, 2018. Available from: http://world wide web.caa.co.uk/Aeromedical-Examiners/Medical-standards/Pilots-(EASA)/Weather/Respiratory/Respiratory-guidance-material-GM/.

-

Sudduth CL, Shinnick JK, Geng Z, McCracken CE, Clifton MS, Raval MV. Optimal surgical technique in spontaneous pneumothorax: a systematic review and meta-assay. J Surg Res. 2017;210:32–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2016.10.024.

-

MacDuff A, Arnold A, Harvey J, Group BTSPDG. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: British Thoracic gild pleural illness guideline 2010. Thorax. 2010;65 Suppl 2(Suppl ii):ii18–31. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2010.136986.

-

Lardinois D, Vogt P, Yang Fifty, Hegyi I, Baslam K, Weder West. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs decrease the quality of pleurodesis after mechanical pleural abrasion. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;25(v):865–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.01.028.

-

Tschopp JM, Bintcliffe O, Astoul P, Canalis East, Driesen P, Janssen J, et al. ERS chore force argument: diagnosis and treatment of principal spontaneous pneumothorax. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(2):321–35. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00219214.

-

Westward JB. Why doesn't the elephant have a pleural space? News Physiol Sci. 2002;17:47–50. https://doi.org/x.1152/nips.01374.2001.

-

Cardillo Grand, Facciolo F, Regal M, Carbone L, Corzani F, Ricci A, et al. Recurrences post-obit videothoracoscopic handling of primary spontaneous pneumothorax: the role of redo-videothoracoscopy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;nineteen(four):396–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1010-7940(01)00611-10.

-

Immature Choi S, Beom Park C, Wha Song S, Hwan Kim Y, Cheol Jeong Due south, Soo Kim K, et al. What factors predict recurrence afterward an initial episode of chief spontaneous pneumothorax in children? Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;20(6):961–7. https://doi.org/10.5761/atcs.oa.13-00142.

-

Uramoto H, Shimokawa H, Tanaka F. What factors predict recurrence of a spontaneous pneumothorax? J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;7:112. PMCID: PMC3488480. https://doi.org/ten.1186/1749-8090-7-112.

-

Imperatori A, Rotolo N, Spagnoletti M, Festi 50, Berizzi F, Di Natale D, et al. Take chances factors for postoperative recurrence of spontaneous pneumothorax treated by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgerydagger. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2015;20(five):647–51; discussion 51-2. https://doi.org/ten.1093/icvts/ivv022.

-

Jeon HW, Kim YD, Kye YK, Kim KS. Air leakage on the postoperative mean solar day: powerful factor of postoperative recurrence after thoracoscopic bullectomy. J Thorac Dis. 2016;eight(1):93–7. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2016.01.38 PMCID: PMC4740151.

-

Chase I, Teh East, Southon R, Treasure T. Using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) following pleurodesis. Collaborate Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2007;vi(i):102–4. https://doi.org/10.1510/icvts.2006.140400.

-

Haws MJ, Kucan JO, Roth Air conditioning, Suchy H, Dark-brown RE. The furnishings of chronic ketorolac tromethamine (toradol) on wound healing. Ann Plast Surg. 1996;37(2):147–51. https://doi.org/x.1097/00000637-199608000-00005.

-

Muscara MN, McKnight West, Asfaha S, Wallace JL. Wound collagen deposition in rats: effects of an NO-NSAID and a selective COX-2 inhibitor. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129(iv):681–six. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0703112 PMCID: PMC1571897.

-

Ben-Nun A, Golan North, Faibishenko I, Simansky D, Soudack 1000. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications: efficient and safe treatment following video-assisted pleurodesis for spontaneous pneumothorax. World J Surg. 2011;35(11):2563–seven. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-011-1207-3.

-

Lizardo RE, Langness South, Davenport KP, Kling K, Fairbanks T, Bickler SW, et al. Ketorolac does not reduce effectiveness of pleurodesis in pediatric patients with spontaneous pneumothorax. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50(12):2035–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.08.017.

-

Elsayed HH, Hassaballa A, Ahmed T. Is video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery talc pleurodesis superior to talc pleurodesis via tube thoracostomy in patients with secondary spontaneous pneumothorax? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2016;23(iii):459–61. https://doi.org/ten.1093/icvts/ivw154.

-

Ling ZG, Wu YB, Ming MY, Cai SQ, Chen YQ. The consequence of pleural abrasion on the treatment of primary spontaneous pneumothorax: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2015;ten(6):e0127857. https://doi.org/10.1371/periodical.pone.0127857 PMCID: PMC4456155.

-

Chen JS, Hsu HH, Huang PM, Kuo SW, Lin MW, Chang CC, et al. Thoracoscopic pleurodesis for master spontaneous pneumothorax with high recurrence risk: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2012;255(3):440–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824723f4.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Writer data

Affiliations

Contributions

PG initiated the idea, collected all previous patient information, provided the first draft of the manuscript, and finalized the manuscript for submission; EVR contributed to the writing of the case presentation and did the main literature search; ND provided all patient information, prepared the figures and reviewed the manuscript; TO is the surgeon performing both interventions, and provided technical details of the patient history; JVA analysed the histological samples and contributed to the writing. All authors read and approved the last manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The patient gave informed consent to publish his instance report data as well as the radiological and videoscopic images.

Competing interests

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatever medium or format, as long as yous give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party cloth in this article are included in the article'due south Artistic Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is non included in the commodity's Artistic Eatables licence and your intended employ is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted employ, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/four.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/null/one.0/) applies to the information made bachelor in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

Virtually this article

Cite this article

Germonpre, P., Van Renterghem, E., Dechamps, N. et al. Recurrence of spontaneous pneumothorax six years after VATS pleurectomy: evidence for germination of neopleura. J Cardiothorac Surg 15, 191 (2020). https://doi.org/ten.1186/s13019-020-01233-nine

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-020-01233-9

Keywords

- Primary spontaneous Pneumothorax

- Pleurectomy

- Recurrence

- VATS

- Pleural regeneration

Source: https://cardiothoracicsurgery.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13019-020-01233-9

0 Response to "Can You Get Spontaneous Pneumothorax Again"

Postar um comentário